Over a decade ago, the HSE published ‘HSG274 - Part 2’ in 2014, which introduced a slightly different way of monitoring hot water systems (this document was reissued in 2024).

The What….

Previously, HSE guidance on recirculating hot water systems required water temperatures to be monitored at the nearest and furthest outlets on a distribution system; otherwise referred to as the ‘sentinel points’. Since then, it has been recognised that recirculating hot water systems, although designed to minimise deadlegs, can become unbalanced, creating such deadlegs that may not be identified for a significant period of time.

In the updated guidance, the HSE re-defined these ‘sentinel points’ as:

“…the far sentinels are the return legs at a point towards the end of the recirculating loop”.

Thus, encouraging testing at the points of a recirculating hot water system where these unknown deadlegs may be lurking. The guidance advises that the water temperature at the sentinel points on the main legs of the distribution system should be checked monthly. These legs are referred to as the principal loops.

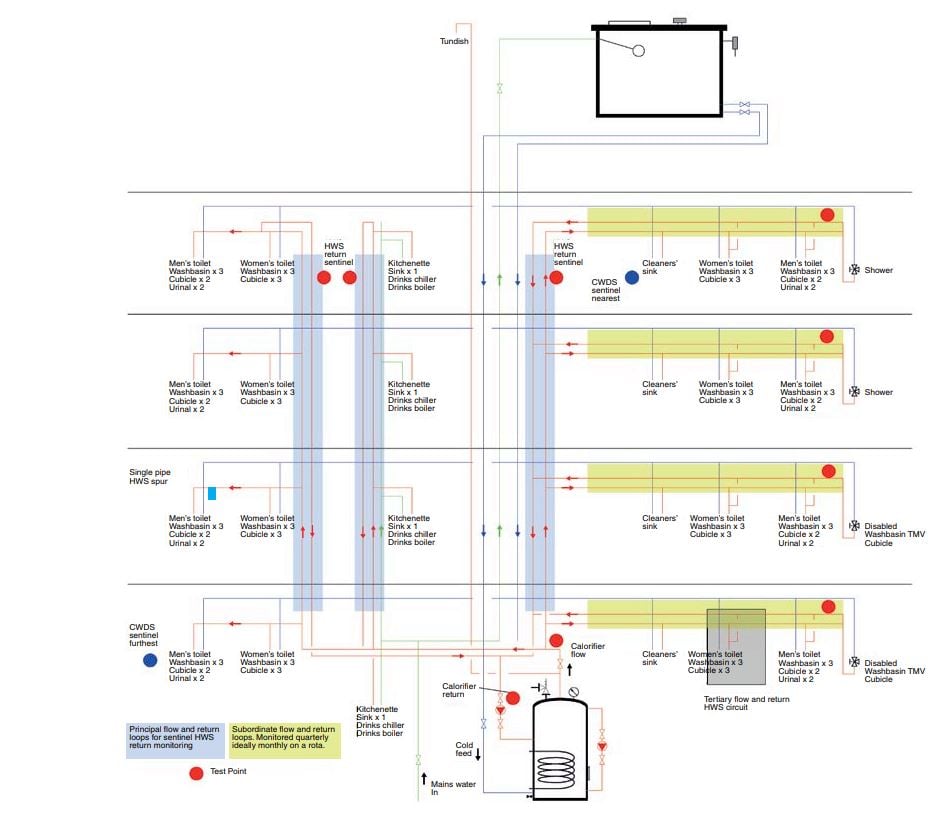

Larger and more complex hot water systems may include additional circuits branching off the principal loops. These are known as subordinate loops. However, we are not done yet! The guidance requires us to go further and identify all of the hot water circuits, including those that feed only one or two outlets, these are known as tertiary loops [see figure 1].

Under HSG274 Part 2, the water temperature at the furthest point on each subordinate loop should be tested every three months, and a representative number of tertiary loops should be tested on a rotational basis throughout each year.

The Why….

Let’s take a moment to explore our experience of return loop temperatures. Often Legionella risk assessors and water hygiene consultants find that the temperature of hot water return pipework behind an IPS panel, below a hand basin or in the roof space is tepid, indicating inadequate circulation or even, in some cases, no flow at all!

As a reminder, the key conditions that support the growth of Legionella are as follows:

- water temperatures between 20 - 45˚C;

- poor circulation and water flow;

- available nutrients.

It has been identified that recirculating hot water systems have the potential to create the environments listed above, and when left stagnant, these return loops have been implicated in Legionnaires’ Disease outbreaks as the root cause.

Recirculating hot water systems rely on a circulation pump in a single location, typically near the source water heater, that pushes or pulls water around the distribution system. Where these systems have multiple legs, it is easy to see how the circulation may differ between them. Also, where systems have been altered and new loops added, balancing these systems can be a difficult task. In some cases, systems may contain “dead” loops, in which circulation is less effective or even non-existent. This creates zones where the water temperature can fall in to the danger range of 20 - 45˚C.

Hidden Danger…

Checking hot water temperatures at the furthest outlets rather than at the furthest point in the return loop can give you a false indication that the system is circulating effectively. What can really be happening is that the water is being pulled along the system from the source water heater by opening the tap during testing or by other outlets in the area, but as soon as the tap is turned off, the system stops circulating, becoming a “dead-leg” again. The temperature of the hot water system when no outlet is open would only be known by taking the surface temperature of a circulating loop. Non-compliant temperatures will indicate poor system circulation and therefore dead-legs; a compliant temperature at these points indicates good system circulation and that all outlets on that loop should reach the required temperature (50°C or 55°C) within the given one minute of running.

The Where….

‘HSG274 - Part 2’ has two schematic diagrams showing where these principal, subordinate and tertiary loops are located on two different hot water systems. [see Appendix 2.4 on page 57 and Appendix 2.5 on page 58]. Figure 1 below is one of the examples taken from the HSG274 part 2.

Figure 1.

Every hot water system is different; therefore, each hot water system will have different sentinel points. It is important that each leg of the hot water system is identified, categorised into loop type correctly and that this information is used to inform the monitoring programme for the system. Note that not all recirculating hot water systems will include all three types of loops.

Each month, hot water temperatures should be taken on the flow and return to the hot water heater and on each principal loop. In Figure 1, these are indicated by the shaded blue areas. Principal loop temperatures should be recorded from the surface of the return pipework close to where the furthest subordinate loop branches off, as indicated by the red dots in the Figure 1.

Each quarter (ideally on a rolling monthly programme), a temperature should be taken from each subordinate loop. These are indicated by the shaded yellow/green areas in Figure 1. Similarly, subordinate loop temperatures should be recorded on the return pipework after the point where the last flow connection to a tertiary loop or outlet has been made. If it is not practicable to gain frequent access, remote sensors can be installed to give live, constant temperature data.

Lastly, a representative number of tertiary loops should be checked on a rotational basis. These are indicated on Figure 1 as the shaded grey area. These checks could be incorporated into annual TMV servicing.

In each case, there is no need to run outlets for a period of 1-minute before testing. In fact, the temperature of the pipework should always be greater than 50˚C (55˚C in healthcare buildings), so the temperature is recorded without any additional draw off from the system.

The How….

Finding all these loops is no mean feat and will require some working out. Water system schematics, ‘as-fitted’ drawings and a physical check will be needed to pinpoint these locations, especially on complex systems, such as those in hospitals, care homes, schools and large municipal buildings. The most efficient way of doing this is to have accurate ‘as-fitted’ drawings. These will show the exact layout of a water system, showing each loop and outlet.

If these drawings are not to hand, then a basic schematic drawing is the next best thing (potentially supplied with a Legionella risk assessment). These will show diagrammatically where each outlet is and where it is fed from. What it probably won’t show is the exact location of each circulation loop, so additional investigation is needed. Once these points are identified, they can then be added to the schematic and temperature monitoring programme.

If these drawings are not to hand, then a basic schematic drawing is the next best thing (potentially supplied with a Legionella risk assessment). These will show diagrammatically where each outlet is and where it is fed from. What it probably won’t show is the exact location of each circulation loop, so additional investigation is needed. Once these points are identified, they can then be added to the schematic and temperature monitoring programme.

It is important to note that it is outside the scope of a Legionella Risk Assessment to identify sentinel points, just to appraise those already identified. However, this exercise could be tied in with a risk assessment.

Once sentinel points have been correctly identified, it is argued that fewer temperature checks will be required in total when compared to a programme designed to comply with the guidance pre-2014. Furthermore, as no outlets need to be run before testing, the updated regime lends itself well to remote temperature monitoring systems i.e. through an established building management system or an independent, smaller-scale temperature monitoring system. This requirement has pushed organisations to utilise technology and install temperature sensors within new builds and refurbishments. This allows constant temperature monitoring, fitted with alarms to alert failures, as opposed to an isolated monthly check and reliance on user complaints.

What happens next….

As we have discovered, the HSE have identified a problem relating to the monitoring of hot water systems and the potential for circulation imbalance to cause undetected areas of poor temperature compliance. As such, the HSE has given guidance on how to monitor recirculating hot water systems so that circulation issues are readily detected.

It is now up to the Responsible Person and/or the Water Safety Group to ensure that the principal, subordinate and tertiary loops are correctly identified. They should ensure that the identified sentinel points are monitored to confirm the circulating hot water system, which is the traditional control regime for Legionella control, remains effective.

Feel free to reach out if you have any questions about this blog or if you would like to consult with one of our experts for further advice on water hygiene.

Editors Note: The information provided in this blog is correct at date of original publication - December 2018. (Revised December 2025)

© Water Hygiene Centre 2025